| |

mericans have

always been more and at the same time less than what we pretended.

With the quickening approach of the twenty-first century, greater

numbers of us are giving testament to this inescapable fact,

challenging the cozy myths by which America has been ritually

defined. Who are we? Who are we becoming? Who and what have we

been? In the next century, can we even continue to speak (could

we ever?) of a collective "we"? For the longest, of

course, these questions had simple answers.

America was white. America was male. America

was heterosexual. America was Christian. America, above all,

was a melting pot into which diverse cultural communities gleefully

descended to achieve the social and ideological transformation

necessary for inclusion within the American Dream. That many

of us--marginalized and oftentimes invisible Americans of African,

Asian, Latino and Native descent, as well as women and the working

poor--never quite melted and metamorphosized according to this

traditional prescription for social progress, hardly mattered.

The great distance between the Dream and our actual lives was

not due to any fault in the Dream: the defect was in us. The

Dream thus survived intact, its seductive power sustained by

America's stubborn refusal to look too closely at the hidden

but terrible costs of "the good life" and at who actually

could--much less wanted to--afford it.

The sixties, of course, spotlighted the

complex oppressive regime of thought, politics and culture which

underlay the myth of America. For the first time in U.S. history,

the ideological fabric of white heterosexual patriarchy was exposed

for the life-constricting straightjacket it had always been.

Despite conservative attempts during subsequent years at repair,

the old social fabric has been steadily unraveling. Thus we have

arrived at this present moment, wherein a nation historically

averse to serious introspection now exhibits--in its politics

and popular media as well as its universities--an almost obsessive

reflexive preoccupation with our national identity.

To be expected, much of the current debate

is simply a re-hash of old opinion--an attempt to forcefully

rebut and undercut the de-centering politics of radical multiculturalism

(i.e., the kind of multiculturalism where difference actually

makes a differ-ence). Bring back the melting pot. Restore "traditional

values." Re-institute prayer in schools. Preserve the primacy

of Western civilization (the only one that matters anyway). And

not least, protect that critical bedrock of American greatness,

"the American family": such pronouncements reveal an

intense, even pathological desire to perpetuate a thoroughly

obsolete myth of America, and through this, a repressively orthodox

system of sociocultural entitlement.

hile the ideas of conservative/fundamentalist

America are hardly new, the typically strident pitch with which

such ideas are now being argued betrays how acutely anxious many

conservatives have come to feel, due to both real and anticipitated

loss of privilege and power. What is more, arch-conservative

rhetoric--as should be evident to anyone watching our presidential

elections for the past quarter century--has found a certain public

resonance. Difference, in the traditionalist outlook, has been

regressively equated with disunity; and disunity with profound

social chaos and collapse. Just as nature abhors a vacuum, so,

it seems, do many Americans with regard to the social-political

myths by which they organize and make sense of their lives. Even

a fundamentally flawed, repressive, inequitable social order

seems to many better than none at all. A clear imperative thus

confronts American progressives--that intricate (and frequently

fragile) web of communities comprised of people of color, feminists,

gays and lesbians, the poor and working class, as well as ethnic

whites who value ethnicity, indeed all who have been systematically

disenfrancised and dehumanized under the once ascendant "traditional

values" of pre-Civil Rights America.

It's no longer enough, if it ever was,

to critique interlocking systems of oppression without offering

affirming alternatives of how society should and can reconstitute

itself. As we move into the inevitably more demanding multilingual,

multicultural environment--both nationally and globally--of the

next century, our greatest task will be an inversion of the commonly

assumed equivalence between difference and disunity. We must

re-write this equation, demonstrating again and again that unity

does not require unanimity, that unity--that is, a sense of social

cohesion, of community--can and does derive from the expression,

comprehension, and active nurturing (and not merely tolerance

or fetishization) of difference.

This is the new standard of civilized life

that now demands our urgent labor, a new world order, if you

will, that subverts traditional conceptions of social order:

a standard which in effect subverts the meaning of the word "standard"

itself. For the new order must be comprised of multiple standards:

shifting, open-ended, dynamically transforming, so as to engender

ways of thinking and living that privilege no one set of cultural

differences over another but affirm virtue in all.

This perspective forms the key inspiration

and overarching theme in STANDARDS. Page after page eloquently

testifies to the commitment of a new generation of America's

best and brightest to shaping a radically redefined vision of

our future, where old repressive dualisms of race, class, sexuality,

gender and nationality no longer reign--a future in which not

merely some but all of us are free to explore and express our

richest humanity.

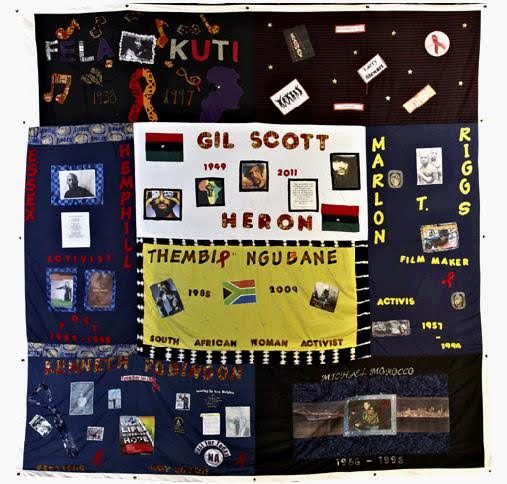

Marlon Riggs

Oakland, 1992

|

|

Nextdoor Support (

Nextdoor Support (

![[DIR]](Gmail%20-%20Nextdoor%20%20When%20a%20neighborhood%20website%20turns%20unneighborly_files/U2iVpRJDQFe5x32RnIm6OVAsWdB-GU-jVen5LvftY6FRvcMdE1rM8i434ZFo.gif)

![[DIR]](Gmail%20-%20Nextdoor%20%20When%20a%20neighborhood%20website%20turns%20unneighborly_files/3xQo2DvCX1N3BA6WePdYtQbk309iSwNWuxc78ho7TzEEzsWQiPnhmGtOJZzG.gif)

![[IMG]](Gmail%20-%20Nextdoor%20%20When%20a%20neighborhood%20website%20turns%20unneighborly_files/PaLo67f5x7oeasj5p0Zkk08pW8qZY7SIQ21PfKrngvqgblyIzkIfsuo4iC_x.gif)

![[DIR]](Gmail%20-%20Nextdoor%20%20When%20a%20neighborhood%20website%20turns%20unneighborly_files/tUQkaouVV2yrkvOQokI0cHo7QiZgpx40JhkhGBbz3cjCBTcj_0pJ9_dnqzyv.gif)

![[SND]](Gmail%20-%20Nextdoor%20%20When%20a%20neighborhood%20website%20turns%20unneighborly_files/5E8h5NjixLPDQKK6FAxiPPtgHMpDdyXxaWYqvUnGbdoZj5Qa298WP_dlA-UT.gif)

![[TXT]](Gmail%20-%20Nextdoor%20%20When%20a%20neighborhood%20website%20turns%20unneighborly_files/Nv-AN6AD_p-JbCfOjs4N3HihBvhor00FQL41JxCPF-9AWpfVKPMueWvgB_JS.gif)

![[IMG]](Gmail%20-%20Nextdoor%20%20When%20a%20neighborhood%20website%20turns%20unneighborly_files/TDtIC4AGUiYCoheijUTYiso17poJfP8QSGO7TyCcsvNO5awEWlsEp3ZZHGgB.gif)

![[TXT]](Gmail%20-%20Nextdoor%20%20When%20a%20neighborhood%20website%20turns%20unneighborly_files/Hn8GxsoRhf73UFyn_VxbUg2BeyBt1VpAmp8qEltEyK6Gh1d8fECEpGWhcxF6.gif)